The global narrative surrounding climate tech is currently dominated by a single, shimmering promise: Blockchain will democratize the carbon markets. By tokenizing carbon credits, we are told, we can strip away the opaque layers of traditional finance, eliminate predatory brokers, and allow a direct flow of capital from a Silicon Valley tech giant to a smallholder farmer in Kenya. On paper, it is the ultimate win-win for decentralization and the planet.

If blockchain carbon markets are designed for always-on connectivity, financial literacy, and self-custody, they will systematically exclude the very communities they claim to empower. However, as we rush toward this “On-Chain” future, we are ignoring a burgeoning irony. In our effort to dismantle traditional gatekeepers, we are inadvertently erecting a digital wall. This is the Digital Divide Paradox: the very communities most capable of generating high-quality, nature-based carbon credits-indigenous tribes, rural farmers, and conservationists in the Global South-are the ones least equipped to navigate the technical labyrinth of the blockchain.

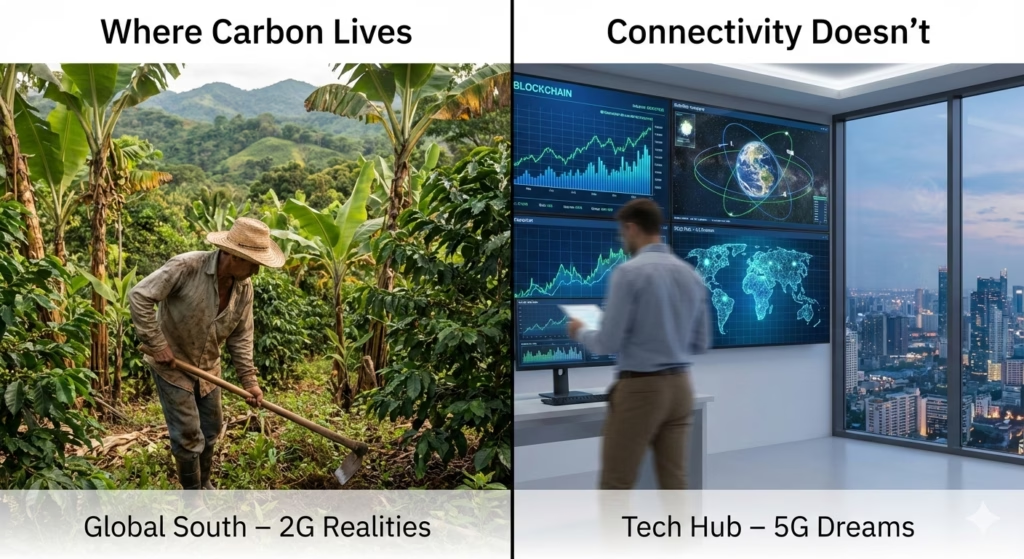

The primary source of “Nature-Based Solutions” (NbS) resides in the world’s most remote biodiverse regions. These are areas where carbon sequestration isn’t just a corporate buzzword; it’s the result of regenerative agriculture and forest stewardship.

Blockchain systems, however, are built on the assumption of seamless connectivity. To interact with a decentralized ledger, a project developer typically needs:

In reality, many communities in the “Carbon Belt” (regions around the equator with high sequestration potential) still operate in low-bandwidth environments. When a carbon credit platform requires high-resolution satellite imagery uploads or real-time IoT sensor data to mint a token, the local steward is immediately disadvantaged. The irony is sharp: The closer you are to the carbon, the further you often are from the ledger.

Blockchain’s greatest marketing point is “disintermediation”-the removal of the middleman. But for a community leader in a rural village, “being your own bank” is a terrifying proposition.

Understanding private keys, gas fees, seed phrases, and liquidity pools requires a level of digital literacy that remains a luxury. When we replace a traditional carbon broker with a complex smart contract interface, we haven’t necessarily empowered the farmer; we have simply traded one type of gatekeeper for another.

We are already seeing a new class of intermediaries: technical consultants who bridge the gap between the forest and the blockchain. While many are well-intentioned, this knowledge asymmetry creates a power vacuum. If a community doesn’t understand the underlying tokenomics of their own carbon credits, they risk:

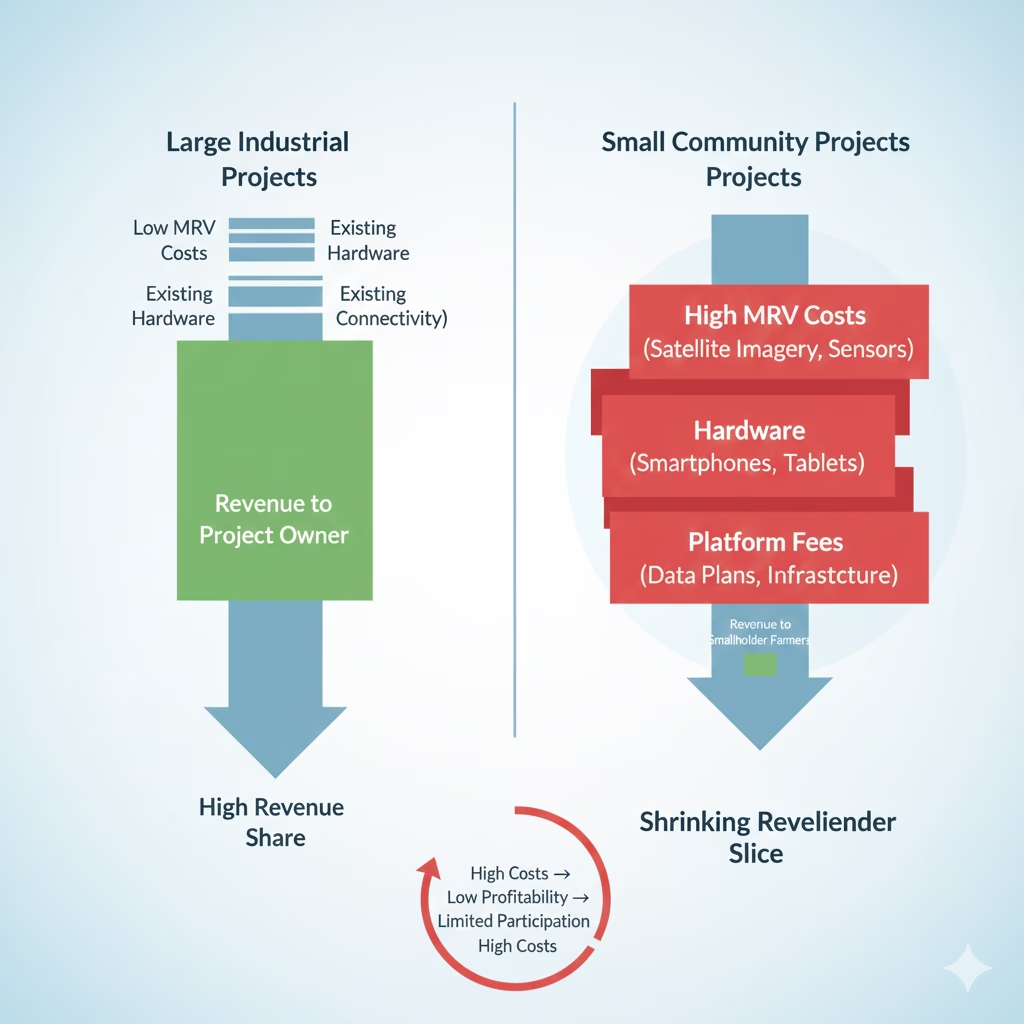

While blockchain promises to reduce transaction costs and eliminate rent-seeking intermediaries, the reality for small, community-led carbon projects is often the opposite. The barrier has not disappeared-it has simply shifted upstream into digital onboarding and infrastructure.

For many micro-projects in the Global South, the economics do not scale favorably. In multiple pilot nature-based projects, total onboarding and verification costs-including digital MRV setup, hardware, training, and platform integration exceed USD $3,000 before a single carbon credit is issued or sold. For projects generating only a few hundred tons of CO₂ per year, this upfront burden can erase profitability entirely.

| Expense Category | Traditional Market Barrier | Blockchain Market Barrier |

| Verification | High fees for manual auditors (e.g., Verra, Gold Standard) | High upfront costs for Digital MRV (IoT sensors, drones, satellite data, software integration) |

| Transaction | Opaque brokerage commissions (often up to 30%) | Network “gas” fees (volatile), bridge fees, and exchange slippage |

| Setup | Years of bureaucratic paperwork | Smartphones, data plans, wallets, custody solutions, and technical training |

The result is a financial exclusion loop. Smallholder farmers and indigenous-led projects-often generating fewer than 500 tCO₂ annually-face a harsh reality:

transaction, verification, and digital infrastructure costs can consume over 50% of total project revenue, even on lower-fee Layer 2 networks.

This creates a systemic bias. Large monoculture plantations and industrial-scale forestry projects can amortize these fixed costs across thousands of credits, while diverse, community-based projects are priced out before they ever reach the market. What emerges is a “pay-to-play” ecosystem-one that unintentionally favors scale over stewardship.

In this model, decentralization does not democratize access. Instead, it risks reinforcing the same inequalities carbon markets were meant to solve, only now encoded in smart contracts and platform fee structures.

If blockchain-based carbon markets are to avoid reproducing existing inequalities, inclusion must be treated as a design constraint, not a downstream fix. The goal is not to make communities adapt to blockchain, but to make blockchain adapt to real-world conditions.

Carbon-rich regions are often connectivity-poor. Platforms should be usable in 2G or intermittent network environments, with offline-first data collection and delayed synchronization. High-resolution uploads, always-on dashboards, and real-time validation should be optional-not mandatory. If a system fails without constant connectivity, it will fail the communities closest to the carbon.

Requiring every farmer to manage private keys or wallets creates unnecessary risk. Participation in carbon markets should not depend on self-custody or crypto literacy. Platforms should support custodial, hybrid, or abstracted wallet models where individuals can earn, verify, and receive payments without ever touching seed phrases, gas fees, or exchanges.

Expecting individual smallholders to onboard independently is inefficient and exclusionary. A cooperative “hub-and-spoke” model, where a trusted local entity manages digital infrastructure, MRV tooling, and market access, allows costs to be pooled and bargaining power to be shared. This mirrors successful agricultural and mobile-money cooperatives, translating collective stewardship into collective market participation.

Blockchain should function as back-end infrastructure, not a user experience. Farmers should interact through familiar tools-SMS, mobile money, local cooperatives-while cryptographic guarantees operate quietly in the background. If users must understand the chain to benefit from it, the system has already failed its inclusivity test.

As blockchain carbon markets mature, many well-intentioned projects repeat the same structural mistakes. These anti-patterns do not fail because the technology is flawed, but because the design assumptions ignore real-world constraints.

Requiring farmers or community representatives to manage private keys, seed phrases, or non-custodial wallets introduces unacceptable risk. Lost keys, phishing attacks, or device failure can permanently lock communities out of their own carbon assets. Self-custody should be an option-not a prerequisite.

When project decisions are made exclusively through Discord servers, Telegram groups, or on-chain voting portals, local stakeholders are effectively excluded. Time zones, language barriers, bandwidth limitations, and digital literacy gaps turn “decentralized governance” into a technocratic echo chamber.

Designing carbon tokens around liquidity pools, yield strategies, or speculative price discovery assumes a level of financial literacy that many participants do not-and should not-need. Carbon markets exist to reward stewardship, not to turn farmers into traders navigating volatility and impermanent loss.

MRV architectures that depend on continuous internet access, real-time sensor streams, or frequent high-resolution uploads systematically disadvantage remote projects. Effective systems must tolerate delayed uploads, offline data capture, and low-bandwidth verification without penalizing participants.

When revenue splits, protocol fees, or infrastructure costs are buried in smart contract logic or opaque dashboards, communities lose agency. If a participant cannot easily understand how value flows, the system is not transparent, regardless of how open the ledger may be.

Blockchain is a tool, not a cure. If used blindly, it will mirror the inequalities of the physical world, creating a “green elite” who can afford the tech to trade, while leaving the actual protectors of the earth behind.

The real innovation in carbon markets won’t be a faster consensus algorithm or a more complex token model. It will be the interface that allows a woman in a remote village to be fairly compensated for the forest she protects, using nothing more than the basic phone in her pocket.

To truly democratize the carbon market, we must first bridge the digital divide. Only then can we ensure that the “Internet of Value” actually delivers value to the people who need it most.If your carbon platform cannot be used without a smartphone, a wallet, and a constant data connection, it is not decentralized-it is selectively accessible.